We use cookies and other technologies to personalize your experience and collect analytics.

Teachers and Students

Sanya Kantarovsky

Sanya Kantarovsky

Teachers and Students

24 May – 21 September 2024

Modern Art is delighted to announce a solo exhibition of Sanya Kantarovsky, 'Teachers and Students' at Modern Art, Paris. Presenting a new body of work comprised of paintings and ceramic sculptures, this is the artist's third exhibition with Modern Art.

Honoré Daumier published his titular series of lithographs in the journal le Charivari between 1845–46. With its title Professeurs et Moutards, the choice of words also suggested that the “students” depicted may have also been rascals, little devils—at least something about them had to merit the punishments, the revulsion exhibited by their authority figures. Rebellious, liberatory moments reoccur in the series. The young students subvert the foolish superiority of their elders, who appear pompously stately, perhaps as armatures of the state itself.

A painter is always already a student, a fact that Kantarovsky implies through rhyming with Daumier himself. What happens to knowledge as it’s transmitted and perverted through another subjectivity? The paintings in Teachers and Students approach this question by presenting a group of actors in these two categories, with the artist himself occupying both.

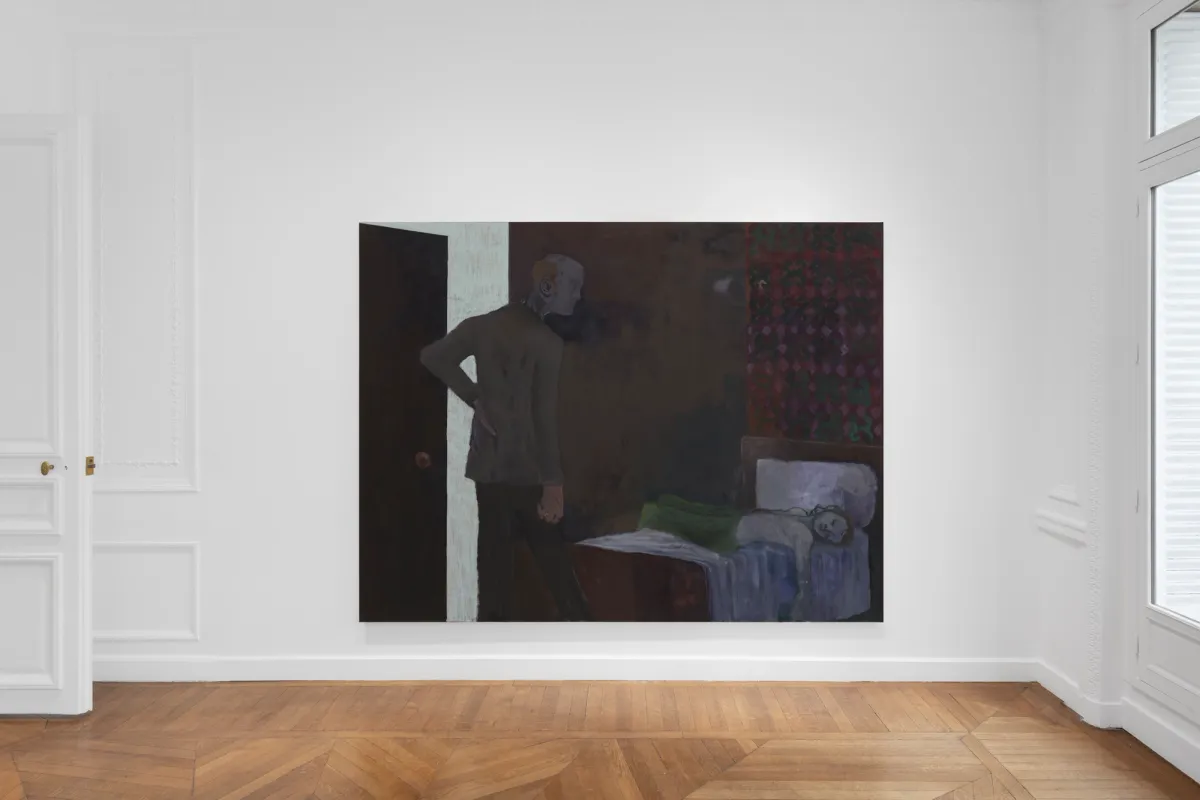

Unlike Daumier’s young rascals, the children here seem resigned to punishment, with the initial act of transgression hidden from view. This omission does not seem to matter much; the focus remains on the child’s consequential state of detachment. Quiet and submissive, the solemnity of the young figures could make one wonder: what is being taught here? Children are rendered in vague, unhardened features, as if to emphasize their youthfulness and vulnerable malleability. The adult figures of authority are at times entirely obscured, with faces that are marbled by swirling, evaporated paint or scumbled out of focus. Their features are marked by receding hairlines and a stiffness of form—a hand that never leaves its pant pocket, shoulder pads fitting just right. One figure casts a heavy shadow across an otherwise flat scene, suggesting the singularity of his stature. Depending on who is asked, these men may be custodians or they may be tyrants.

Is there space in this imbalance for a life lesson? While our teachers and guardians may hold precious knowledge, there is a certain irony witnessed in the stupidity of authoritarianism. In another scene, a young boy’s shoulder acts as a resting surface for a towering forearm and limp wrist, which encases the child’s head against their monolithic torso. An even more quiet form of hostage takes place in a scene painted from memory of Kantarovsky’s Soviet school portrait: a freckled boy, suited, combed and buttoned, his stoic hand raised to formally request permission to speak. It is entirely uncoincidental that this face of good graces is also the one that most closely mimics the composure of an adult scholar. It could be the picture of a lifelong learner, or a childhood robbery.

To my eye, in fact, his paintings look like the product of someone with consummate craft, and if they can sometimes be compositionally awkward, they are always consciously so: Their awkwardness, in other words, is not necessarily deliberate, but is accepted as a necessity given the awkwardness of the feelings the paintings are built to carry. The paintings take an analytical detachment from the disquiet they express, but that detachment does not entirely defend them against being caught up in that disquiet. In part, this disquiet runs on imagery alone.For all his conversancy with the alchemy of paint, Kantarovsky possesses a cartoonist’s or caricaturist’s proficiency with the little nuances of line that sum up a character or an attitude—a facility that can at times be its own reward and, perhaps for that reason, provokes mistrust, even from the artist himself.

– Barry Schwabsky, 2023

Sanya Kantarovsky was born in Moscow in 1982 and emigrated to New York City when he was ten years old, where he continues to live and work. His work has been the subject of recent solo exhibitions at Modern Art, London (2021); Kunsthalle Basel (2018); and Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin (2017). He has participated in recent group exhibitions at Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle (2022); the FLAG Art Foundation, New York (2021); the Drawing Center, New York (2020); the Whitechapel Gallery, London (2020); Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2019); and ICA Boston (2018). His works are held in collections including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo; the Courtauld Gallery, London; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Hirshhorn, Washington, D.C.; LACMA, Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Tate, London; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Press release

Honoré Daumier published his titular series of lithographs in the journal le Charivari between 1845–46. With its title Professeurs et Moutards, the choice of words also suggested that the “students” depicted may have also been rascals, little devils—at least something about them had to merit the punishments, the revulsion exhibited by their authority figures. Rebellious, liberatory moments reoccur in the series. The young students subvert the foolish superiority of their elders, who appear pompously stately, perhaps as armatures of the state itself.

A painter is always already a student, a fact that Kantarovsky implies through rhyming with Daumier himself. What happens to knowledge as it’s transmitted and perverted through another subjectivity? The paintings in Teachers and Students approach this question by presenting a group of actors in these two categories, with the artist himself occupying both.

Unlike Daumier’s young rascals, the children here seem resigned to punishment, with the initial act of transgression hidden from view. This omission does not seem to matter much; the focus remains on the child’s consequential state of detachment. Quiet and submissive, the solemnity of the young figures could make one wonder: what is being taught here? Children are rendered in vague, unhardened features, as if to emphasize their youthfulness and vulnerable malleability. The adult figures of authority are at times entirely obscured, with faces that are marbled by swirling, evaporated paint or scumbled out of focus. Their features are marked by receding hairlines and a stiffness of form—a hand that never leaves its pant pocket, shoulder pads fitting just right. One figure casts a heavy shadow across an otherwise flat scene, suggesting the singularity of his stature. Depending on who is asked, these men may be custodians or they may be tyrants.

Is there space in this imbalance for a life lesson? While our teachers and guardians may hold precious knowledge, there is a certain irony witnessed in the stupidity of authoritarianism. In another scene, a young boy’s shoulder acts as a resting surface for a towering forearm and limp wrist, which encases the child’s head against their monolithic torso. An even more quiet form of hostage takes place in a scene painted from memory of Kantarovsky’s Soviet school portrait: a freckled boy, suited, combed and buttoned, his stoic hand raised to formally request permission to speak. It is entirely uncoincidental that this face of good graces is also the one that most closely mimics the composure of an adult scholar. It could be the picture of a lifelong learner, or a childhood robbery.

For more information, please contact Charles Ndiaye (charles@modernart.net).