We use cookies and other technologies to personalize your experience and collect analytics.

Simon Bill

OOO

5 May – 4 June 2006

Press release

Five years ago Simon Bill stopped painting and started work on a novel, entitled BRAINS, about a painter's experiences as artist-in-residence at a neurology clinic.

IC In 2001 when most of the works included in the show were made, Patricia Ellis wrote about your work referencing it as a skewed ‘Petri dish of experimentation1. This description could relate to both the shape and the idea of each work being one self-contained exploration of what you can do with a medium on any given day and so if each piece is seen in this way, do they inherently exclude the idea of progression for you as a maker?

SB What's nice is to go into the studio of a morning with the sense that you could do just about anything. And if that thing you do is different from what you did the day before, or will do the next day, what you have is a series of dead-ends stretching off into infinity.

IC Do you ever go back to a form within new works or do you have a rule not to retrace old steps?

SB I've frequently caught myself being repetitious or 'consistent' but there's no actual rule against it. It's just that whenever I'm doing one sort of picture I feel like doing another sort as soon as possible afterwards. So if I'm doing something careful with a tiny sable brush I want to do the next picture with a shotgun or some tie-dye. You're always after something the likes of which haven't yet been seen. It's more a matter of temperament than of rules.

IC Is there an opposition within you about what you want to make, are you satisfying different interests and preoccupations within each work?

SB As an artist you've got a large but not limitless box of tricks to draw from, a history of tropes and devices and conceits, and your task is to deploy these given components in a way that transcends their second-handedness. You want to campaign simultaneously on as many fronts as possible, in a word, to experiment, and the result you're after is to be able to look at the thing and think 'Well, I've definitely never seen one of those before.'

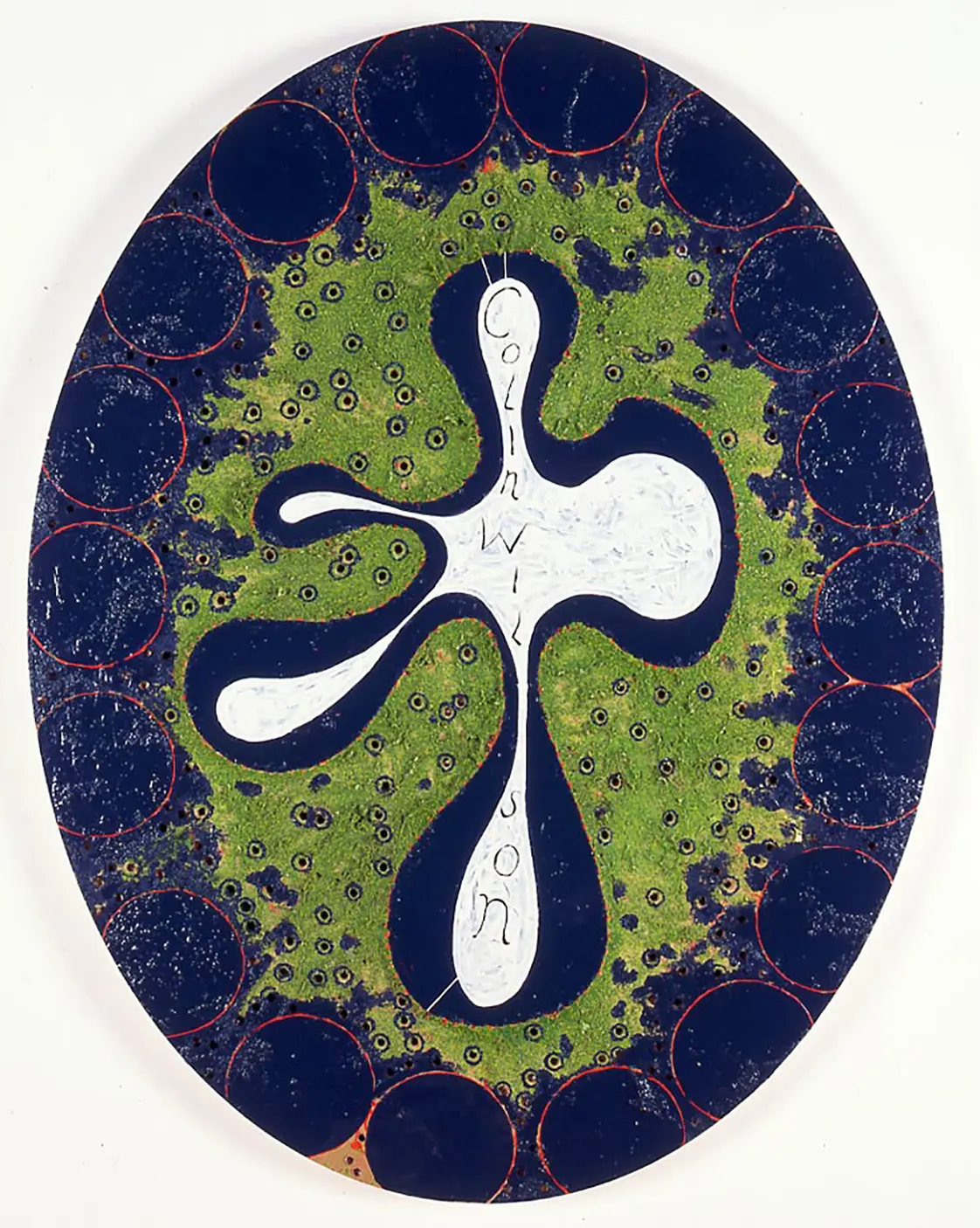

IC Formally speaking, the oval is a perfect shape; no awkward end, no harsh edge. When the lines fall off the surface where do they go, is there a beyond to the edge of the oval?

SB The oval does have that property; that it's easy to feel you're looking through it, like a porthole or a telescope. Something else it does is provide a bit of continuity and a clear physical limit to set off the incoherence of style and subject matter. Imagine how irritating and impractical it would be if I'd chosen to use nothing but pentagrams or rhombuses.

IC In terms of this context and tradition is it important to you that your work is classed as painting as opposed to sculpture?

SB There's a lot of three-dimensional action, and even the flattest ones ought to register both as objects and as paintings. As to being a self-declared ‘painter’ … embracing it as a vocational and ideological title? there are days when I like the sound of it, others not. I certainly don't think painting has any special right to exist and so neither, by implication, do painters.

IC You have spent the last five years writing, had written language always been present within your physical works or do you see them as entirely separate practices?

SB The paintings are the visual equivalent of a made up language. They approximate the conditions of meaning. And there's something analogous going on in the use of words the titling. For example I did a painting of a monkey, and some time later found a perfect title for it on a scrap of paper in an old jacket. 'Threw a Monkey in the Sea' is from Alan Partridge. I must have heard him say that, thought 'That's brilliant', and written it down. The painting was done later, and, so far as I'm aware, independently. There's a painting in the show called '90% Fat Free', for no good reason.

IC Does writing now have something for you that painting doesn’t?

SB There are far too many interesting things in the world to allow a person NOT to be inconsistent. The reason I've been writing is because it's incredibly interesting, and the reason I've been writing about neuroscience is that that it's outstandingly interesting. Everything about this work, the painting and the change from painting, is to do with a restless curiosity, and finding ways of accommodating that restlessness. There'd be thousands more paintings if I could write and do painting at the same time. And I could probably bore you to death on a impressive range of subjects, the structure of the retina; dress-codes of the original skinheads; the English longbow [1350 to 1500]; post-war Anglophone philosophy; the Bowie knife; early and late Titian. And so on, and so on.